When’s the last time you spent your weekend obsessively counting syllables on your fingers? Or trying to find a word that rhymes with fish that is both esoteric and concrete? I know, that sounds like the best weekend ever!

You too can panic as you try to figure out whether enmity has two syllables or three or if sieve rhymes with leave or shiv. All you need is the ever intimidating, ever popular, ever obsessive sonnet.

There are two basic kinds of sonnet: Petrarchan and Shakespearian.

Petrarchan

The Petrarchan sonnet is named after the 14th century Italian poet Francesco Petrarca. The man was mad obsessed with a woman named Laura de Noves. So obsessed he wrote 317 sonnets about her. But unlike the guy who comments ‘hawt’ on all of your selfies, Petrarch had a way with words, and he became a well-respected poet and a celebrity who traveled around Europe just because he could. Because of his celebrity and his obsessive sonnets, Petrarch popularized the sonnet as a poetry form.

Writing a Petrarchan sonnet is like arguing with yourself in the shower. The first stanza is made of eight lines (handily called an octave), and offers a question or an argument, or maybe just an observation.

The second stanza is made of six lines (a sestet) and offers an answer to the question, or offers a counterargument (see, just like in the shower) that shifts the message or narrative of the poem.

Italian is apparently a great language to rhyme in, so the Petrarchan sonnet, an Italian form, has a rhyme scheme that’s heavy on rhyme: abba, abba, for your octave and cdecde or cdcdcd for the sestet.

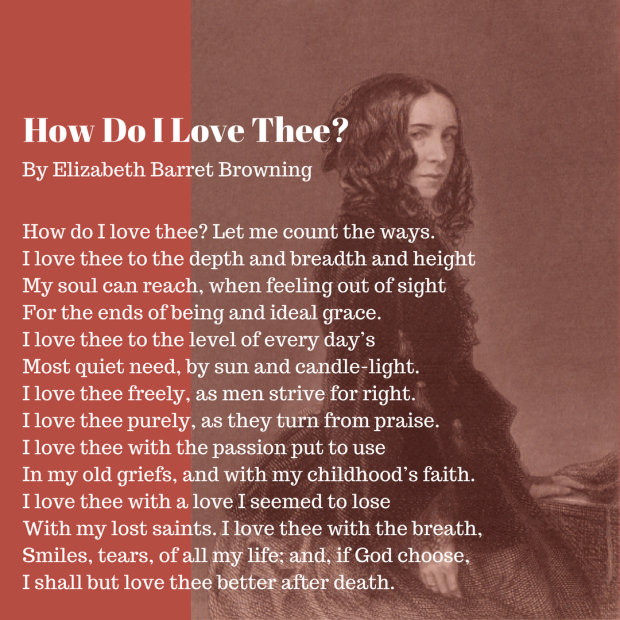

In this sonnet by Elizabeth Barret Browning you can see the rhyme-y rhyme scheme at work:

English is, tragically, not as good a language for rhyming words. So, when the sonnet became popular in England, poets adapted the structure to suit the English language. Which brings us to the…

Shakespearian Sonnet

Hmm, I’m actually not sure who this one’s named after…

But I can tell you that unlike its Italian counterpart, the English sonnet is made of four stanzas: three quatrains (four line stanzas) and one couplet (a rhyming two-line stanza).

Instead of an argument in the shower, the Shakespearian sonnet is more like when your professor rambles for ten minutes only to come to an abrupt and brilliant epiphany at the last moment, that suddenly reframes their ten-minute ramble into something insightful. (We’ve all had those teachers, right? Not just me?)

So, you see, the couplet is crucial, because the couplet is the epiphany. The three quatrains set up an idea, an argument, or a narrative, and the couplet turns the poem on its head and refutes, or concludes that original idea. This kind of dramatic shift or turn in a poem comes with a fancy vocabulary word too: volta.

Real talk, volta is my favorite poetry word. It just sounds so cool! It’s the Italian word for turn, but it always reminds me of a volt of electricity or a bolt of lightning, which is how I remember what it means. The volta electrifies you with new insights.

As mentioned, the rhyme scheme for the Shakespearian sonnet requires less actual rhyming: abab, cdcd, efef, gg.

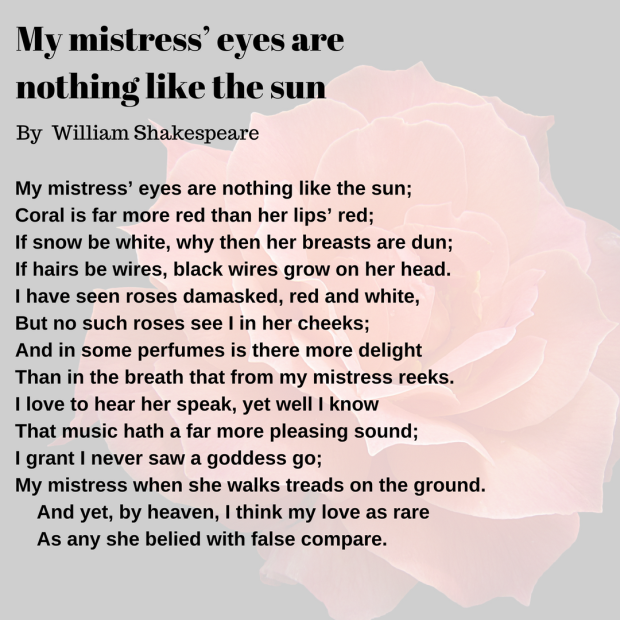

Here’s a sonnet you’ve probably run into before because it’s a great example of a poem that manages to follow all of the form’s constraints and make it look easy:

But wait…there’s more!

Whether poets were writing Petrarchan or Shakespearian sonnets, they traditionally wrote them in iambic pentameter. Like most of our other poetry vocabulary, iambic pentameter is all about numbers.

Meter in poetry is about the rhythm of the words and meter is talked about in units of feet.

Penta=5, so in a poem that uses pentameter, there are five metrical feet in each line.

Feet are units of stressed and unstressed syllables and there are names for all kinds of different combinations of stressed and unstressed syllables, from trochee to pyrrhic. An iamb is an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable (daDUM).

So iambic pentameter just means that there are five sets of unstressed, stressed syllables in each line:

daDUMdaDUMdaDUMdaDUMdaDUM

But don’t stress, breaking rules can be just as powerful and exciting in a poem as following a traditional form exactly.

So whether you want to take someone’s breath away with your perfectly metered and traditionally rhymed sonnets, or you want to shock your readers by breaking from the form in new and exciting ways, sonnets are a great recipe for good poems.

1 Comment